Presented by Evvy Eisen and Exhibit Envoy

Multiply by Six Million is a project by Evvy Eisen and toured by Exhibit

Envoy. All photographs and writings are © Evvy Eisen unless stated otherwise. This online exhibition

is adapted from the physical touring exhibition.

Introduction

“This is important. This is what happened to me and to my family. It should not be forgotten…”

Multiply by Six Million: Portraits and Stories of Holocaust Survivors presents the Holocaust on a human level, as thirty-eight survivors recall their experiences before, during, and after one of the greatest tragedies in human history.

For fifteen years, Evvy Eisen photographed and collected the personal narratives of Holocaust survivors living in the United States and France. During the course of the project, Eisen completed over two hundred portraits. Many of these survivors have since passed away, but their legacy lives on.

Eisen’s images and the stories from each survivor vividly portray the power of human courage in the most desperate circumstances. They are also a testament to the productive lives Holocaust survivors created and their continuing commitment to fight prejudice and injustice. From these portraits and stories, we can be inspired to stand up for those who are targeted today, and to unite against the dehumanization of all men, women, and children.

It is only through personal connections that we can understand the true meaning of such events and prevent them from happening again.

Evvy Eisen, photographer

Multiply by Six Million is a project by Evvy Eisen. The online exhibit is managed by the nonprofit organization Exhibit Envoy, who also tours a physical version of the exhibit. Eisen’s work is in private and museum collections in Europe and the United States, including the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, and the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine in Paris. For additional information about the photographer, her work, and this project, visit multiplybysixmillion.com or evvyeisen.com.

Navigating the Exhibit

In this exhibit, you will meet 38 survivors of the Holocaust. Their stories are split into 5 chapters:

- Searching for Refuge (11 stories)

- In the Concentration Camps (13 stories)

- A Life in Hiding (7 stories)

- The Kindertransport (2 stories)

- Resisting the Nazis (2 stories)

To view each survivor’s full story, simply click on the button that says “Read More…” Start your journey here with Martin’s story.

Martin Kahane

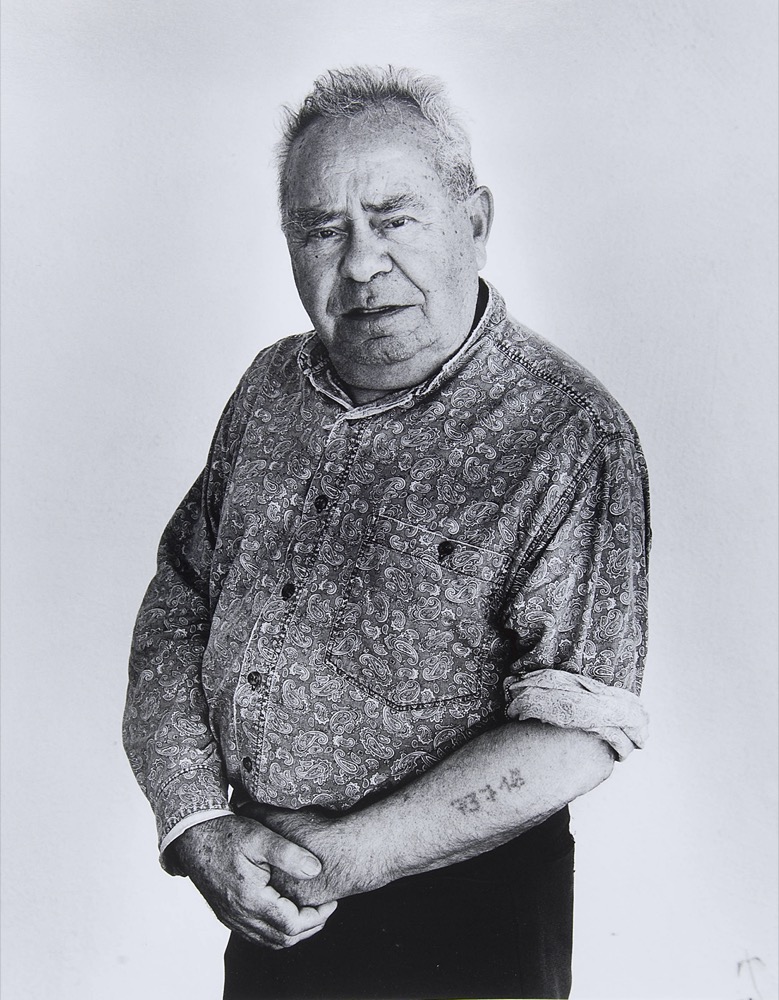

Martin Kahane and his entire family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

I remember when the tanks came into our town – seeing the soldiers in the streets carrying rifles. There was a curfew and the first person I ever saw killed died because he was out after the curfew. He was running and the Germans shot him.

Martin Kahane was born in Ciechanow, Poland in 1923. He lived with his parents, five brothers, and one sister. Ciechanow was a small city in which there were few non-Jewish Poles. Martin’s father was a salesman traveling by horse and cart. His mother took care of the large family, and Martin attended school.

In 1939, the Germans invaded Poland and instituted many restrictions for the Jewish population. At first, the family remained in Ciechanow, and where they were forced to work for the Germans. Three years later, the Germans loaded the entire family onto a train and transported them to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon their arrival, Martin’s mother, father, and brother, David, were separated from the rest of the family. Martin never saw them again.

Martin’s sister was grouped with other younger women, and later died in the camp. Another brother, Avram, had been deported to Auschwitz separately with his wife and child, where they all died. Martin, however, remained with his brothers Sidney and Sam. The number 73718 was tattooed on his arm; Sam’s number was 73719, and Sidney’s 73720. At one point, Martin contracted typhus; he was sent to the camp hospital, where the notorious Dr. Mengele examined him.

In Auschwitz, Sidney was assigned to work with recently arrived transports, Sam worked on sewer lines, and Martin made windows and doors for new homes for German officers.

When the end of war was near, Martin was transferred to a camp in the German village of Buchberg. Eventually, Martin reunited with his brothers Sam and Sidney in the camp, and the American forces liberated them.

After the war, Martin went to Israel on his own. He joined the army there and was decorated for his service in the war for independence. In 1950, he rejoined his brothers in Germany and they immigrated together to the United States, eventually settling in California. Martin worked as a machinist and also operated a laundromat. Married and divorced, Martin was the father of two sons and two daughters. Martin did not raise them to be Jewish, explaining that he lost his faith in God from the war.

Definitions

In this exhibit, you’ll encounter specific words related to the Holocaust. Some definitions follow, provided courtesy of the Holocaust Museum Houston.

Allies: The nations fighting Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy during World War II, primarily Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

Auschwitz-Birkenau: The largest and most notorious concentration, labor, and death camp where 1.6 million people died; located near Oswiecim, Poland.

Concentration Camp: Camps in which Jews were imprisoned by the Nazis, located in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. There were three different kinds of camps: transit, labor and extermination. Many prisoners in concentration camps died within months of arriving from violence or starvation.

Death March: Forced, long-distance marches designed to both transport prisoners between camps and kill them along the way. Prisoners were shot or left behind for dead if they could not keep up.

Displaced Persons Camp: A temporary facility for refugees, or “displaced persons.” From 1945 to 1952, more than 250,000 Jewish displaced persons lived in these camps and urban centers in Germany, Austria, and Italy. These facilities were administered by Allied authorities.

Gestapo: The secret state police of the German army, organized to stamp out any political opposition.

Ghetto: A section of a city where Jews were forced to live, usually with several families living in one house, separated from the rest of the city by walls or wire fences, and used primarily as a station for gathering Jews for deportation to concentration camps.

Holocaust: Term first used in the late 1950s to describe the systematic torture and murder of approximately six million European Jews and millions of other “undesirables” by the Nazi regime from 1933 to 1945. The Hebrew word for the Holocaust is “Shoah.”

Kristallnacht: Also referred to as the “Night of Broken Glass,” this pogrom occurred on Nov. 9-10, 1938 in Germany and Austria against hundreds of synagogues, Jewish-owned businesses, homes, and Jews themselves.

Nazi: Name for members of the NSDAP, National Socialist Democratic Workers Party, who believed in the idea of Aryan (white) supremacy.

SS: Schutzstaffel; the German army’s elite guard, organized to serve as Hitler’s personal protectors and to administer the concentration camps.

The Multiply by Six Million project was partially funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, California Humanities, and the Koret Foundation.

Searching for Refuge

Many Jews tried to flee when the Nazis rose to power. Procuring a visa was a difficult process, and not many countries would accept Jews as refugees. In the stories below, you will hear from survivors who successfully escaped the Nazi regime, and from those who spent the war looking for a way out.

Lotte Stein

Lotte and her family escaped from Austria and spent the war years in England.

Lotte Stein (née Pfeffer) was born in 1921 in Vienna. Her father Maximilian, the owner of a bicycle factory, and her mother, Martha, had considered themselves assimilated Jews. After her mother’s death, when Lotte was seven, she and her older sister were raised mostly by servants, simple and devout Christian women from the countryside. Lotte was not taught about her religious heritage and traditions, but felt that she was different from most of the people around her.

The family had not believed the rumors coming out of Germany at the time, and were sure that those kinds of atrocities could never happen to them because they were Austrians and had blended into the Viennese culture. But when Hitler entered Austria in 1938, they were confronted with the fact that they were Jewish. They suffered the many deprivations and restrictions that the Nazis imposed on the Jews; Jews were forbidden to enter restaurants, coffee shops or sit on benches in the park. They were not allowed to use public transportation and the family car was confiscated. Lotte had to move to the back of her class and, after a few months, was forbidden to attend school all together. She was in constant fear of being arrested and deported.

After living for a year under Hitler’s occupation, Lotte, her father, and her sister were able to utilize family connections and leave for England where they survived the war years. However, they were considered enemy aliens and undesirable subjects, and were not trusted to contribute to the war effort. They were dependent upon refugee organizations, and could obtain only menial jobs. Her grandmother, aunt and uncle were not able to leave Austria in time, and died in concentration camps.

In 1946, Lotte immigrated to America where she married and had two daughters. Lotte was drawn to the Jewish community, slowly finding her way back to her Jewish heritage. Determined to resume the studies she had to abandon in 1938, she earned master’s and doctorate degrees and had a career as a Family Therapist.

My life had become a journey of searching and finding the essence of myself. I felt much more at home in the American multi-cultural society. I felt drawn to the Jewish community and slowly found my way back to my heritage.

Esther Kozlowski

Esther Kozlowski survived the war by moving from one place to another with her baby, living by her wits.

Esther Kozlowski (née Naiman) was born in 1914 in Wodzislau, Poland, where her father ran a lumber business. She fondly recalled times before the war living in a comfortable home with her five siblings and other family members.

Esther was married and, three months before the outbreak of the war, gave birth to a son, Moshe. When the Germans bombed the town, Esther, her husband, her baby and other family members traveled to her in-laws’ farm 60 kilometers away. Conditions on the road were chaotic, but once they arrived, the family felt safe.

When it became common knowledge where the transports of the Jews were going, I decided rather to die from one bullet with my baby than to suffocate in a cattle train.

After two months, Esther and her family returned to Wodzislau, only to find that they could not get into their home and that the family lumber business had been confiscated by a Nazi sympathizer. The Germans were everywhere and Esther became desperate. When it became clear that the Jews were being transported to concentration camps, Esther and her baby fled.

All during the war she moved about, alone with her son, staying in some places for months, in others only for days. The Germans were everywhere. There was often chaos on the roads and Esther and the baby endured terrible hardships.

In 1944, the Russians liberated the village near Treblinka where Esther was working, digging potatoes and writing letters in German for the Polish women whose sons and husbands were in slave labor camps. She was reunited there with her youngest brother. At the end of the war, Esther searched the announcements on the walls of the Jewish committee, but found only the names of her oldest brother and his son. Her husband had been killed in 1943.

Esther and her son left Poland, walking until they reached Germany. They lived in various Displaced Persons camps for five years until they were permitted to immigrate to New York in 1951. Shortly after arriving, she married a man whom she had known in one of the Displaced Persons camps, and they eventually settled in San Francisco.

Richard Kimelman

After hiding in Vienna, Richard Kimelman and his parents escaped to England where they spent the rest of the war years.

Richard Kimelman was born in Vienna in 1926 to Polish-born parents, both of whom were physicians and dentists. When the German Army invaded Austria in 1938, Richard saw tanks, trucks and motorbikes rolling past the apartment, with sirens wailing.

Though Richard was familiar with anti-Semitism both at school and in the streets, where he was attacked by gangs of boys, nothing prepared him for what happened after the German invasion. His father, who had been awarded the Iron Cross in World War I, was among the first to be arrested, and remained a prisoner in Dachau for a year. Richard and his mother hid with a friend until the friend killed himself, and they had to find another refuge. After one year, Richard’s mother courageously managed to speak to the deputy leader of the Gestapo in Vienna, asking to get her husband released. She promised that the family would leave Austria immediately and, with great difficulty, she was able to obtain visitors’ visas to England.

Richard, who didn’t know a word of English when they arrived, received a scholarship to a British boarding school. Once there, he narrowly escaped injury when a German rocket landed a few feet from where he was sleeping, sweeping away the house over his head and leaving him with only minor injuries.

Due to a shortage of medical personnel during the war, Richard’s parents were eventually permitted to work as dentists in a London clinic. He joined them there to go to college, graduating in Engineering from London University in 1946. They decided to settle in England and became British Subjects.

Richard learned that the only survivors from both his parents’ families were an uncle, who was in the Warsaw Ghetto, and his daughter, who survived a jump from a moving train taking her to a camp.

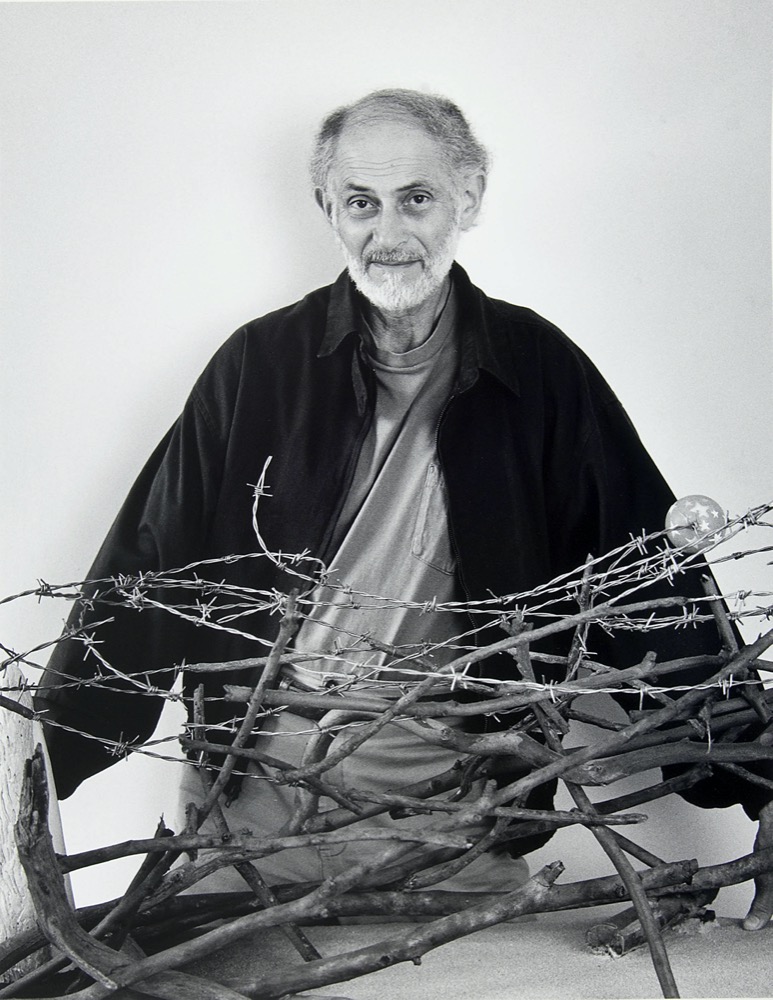

Shortly after the war, Richard met and married Joan Sands. They immigrated to the United States, eventually living in Northern California with their three children. Richard had always been considered artistic but, during the war, attending art school was not a possibility. After a long career as a structural engineer, he became a full-time sculptor.

After visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem, I started to develop a mixed media style of sculpture utilizing barbed wire which expressed my deeper feelings.

Ruth Geoffey

Ruth Geoffey escaped the Nazis by fleeing to Manila, where she spent the war years.

Ruth Geoffey (née Huber) was born in 1915 in Brünn in the former Czechoslovakia. At the outbreak of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian army recruited her father, an officer at the time. Her parents divorced when she was two, and her mother took young Ruth to her family in Berlin, where Ruth grew up.

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Ruth had just finished high school, but the new laws made it impossible for her to attend university. Regardless, Ruth’s family encouraged her to develop her talent for drawing, and she went to art school. Ruth illustrated stories for Jewish papers and worked did fashion design.

Ruth married Joseph Reiner, a journalist, in 1938. Together, they made plans to immigrate to Shanghai.

We left by train on Christmas hoping that the guards would be more lenient because of the holiday. The couple we were traveling with was taken away and was never seen again.

Ruth and Joseph arrived safely in Trieste, Italy with all of their hidden “treasures,” which allowed them to survive until their ship for Shanghai sailed. After Shanghai, they went to Manila. Despite carrying Austrian passports with a “J” marking them as Jews, they were considered “Allies of the Axis” and were not interned.

Life was very difficult for the Jewish refugee community in Shanghai, which was under the leadership of a Rabbi who had escaped from Germany. Because of tremendous inflation, the couple was forced to sell most of their belongings and plant gardens to eat; this garden became their main source of food. During the war, Ruth secured a travel ticket to Shanghai for her mother, who successfully fled to Asia. No other members her family in Czechoslovakia and Germany survived.

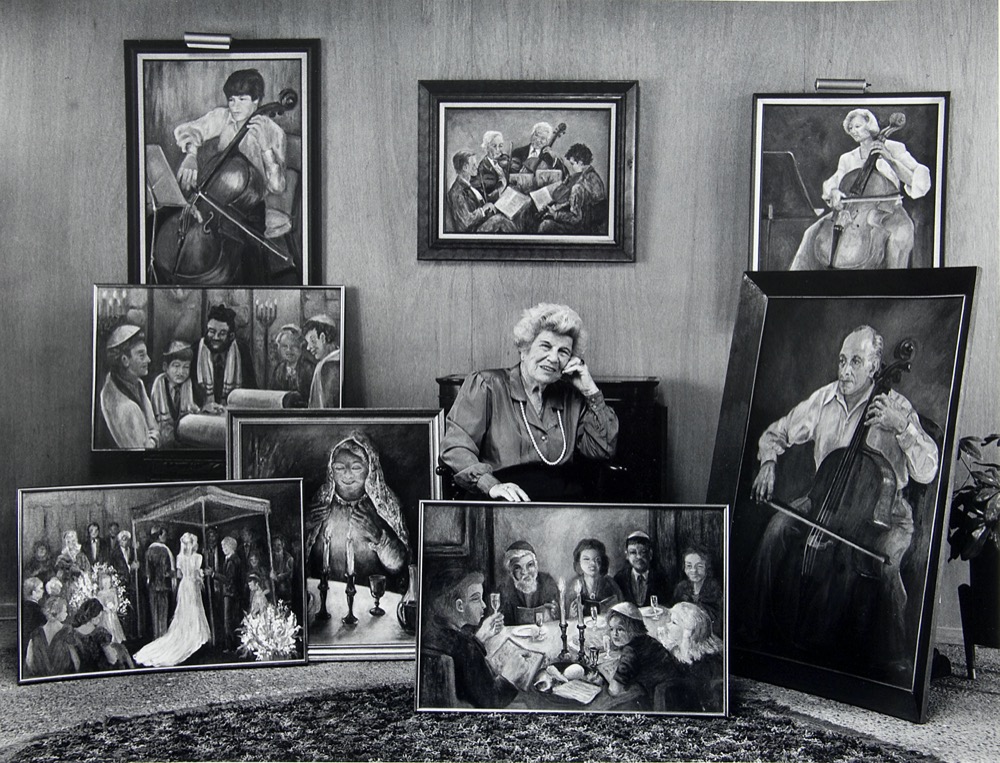

When her husband died in 1945, Ruth remained in Manila. There, she married a Holocaust survivor who had been in several concentration camps. Ruth taught arts and crafts at the American School in Manila, while her husband worked for 20th Century Fox film. They eventually moved to California, where Ruth started painting and received a degree in Fine Arts in 1968.

Later in life, Ruth used her art to paint subjects recalling past times and reviving memories of Jewish traditions. Those topics are the origins of her many paintings surrounding her in her portrait.

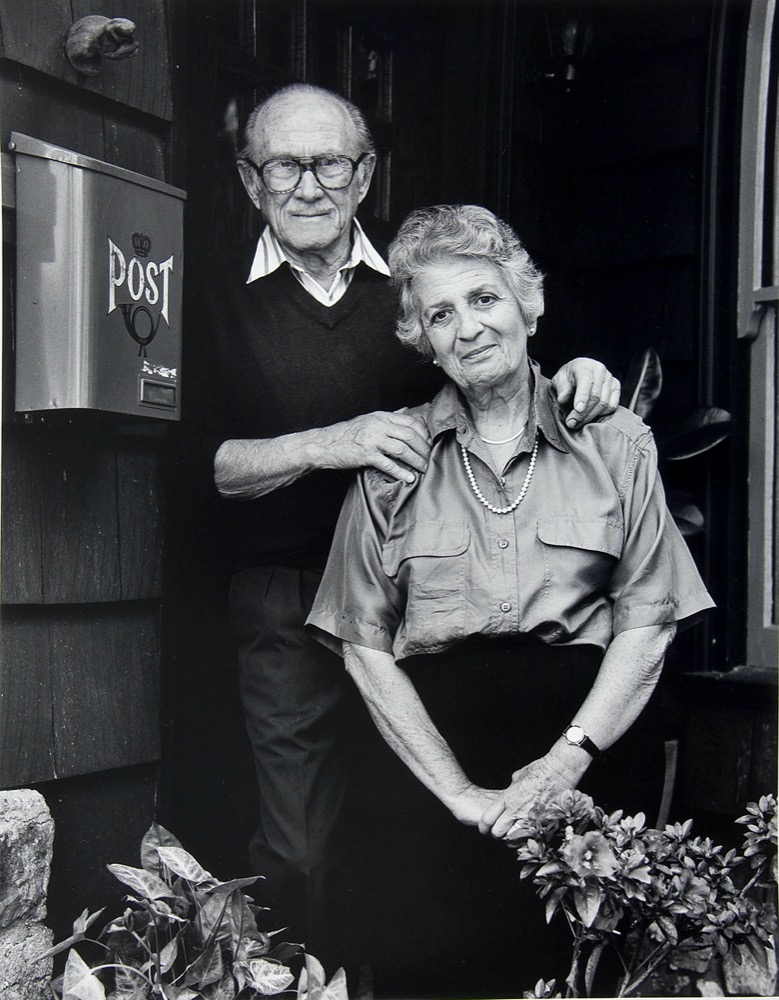

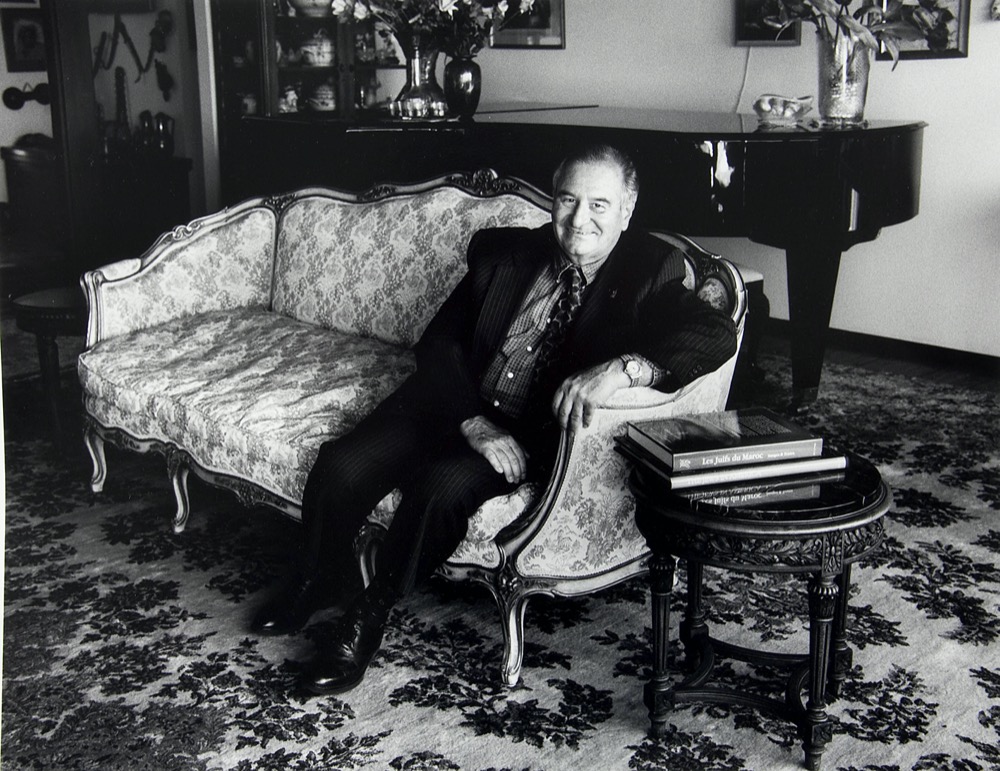

Stella and Elie Tennenbaum

Stella and Elie Jacques Tennenbaum each left Nazi-occupied Europe and headed to Shanghai, which was under Japanese occupation during the war. They met there as fellow medical students.

We lived a life of compassion for every living creature, be they human or animal. Family, above all, was important.

Elie Tennenbaum was born in Krakow, Poland on a memorable day in 1917 — the seventh day of the seventh month, on the Sabbath, the seventh day of the week, at 7:00 PM. An only child, he was raised as an orthodox Jew. Elie attended a Jewish day school and grew up speaking several languages, which he used frequently throughout his life. Although many Poles were virulently anti-Semitic, Elie got along well with some Polish students; they would often warn him if something bad was going to happen.

Jews in Poland were not allowed to study medicine, so Elie moved to Paris for school. After the Nazis occupied the city, Elie was not able to continue his studies, and he managed to immigrate to Shanghai, a free port that was accepting refugees.

Stella Tennenbaum (née Reich) was born in Moravska-Ostrava Czechoslovakia, a coal mining town, near the German-Poland border, in 1916. She lived a comfortable life as an assimilated Jew, participating in sports like fencing, skiing, and gymnastics, and did not experience anti-Semitism when she was growing up. She initially wanted to become an architect, but instead studied medicine in Prague starting in 1934.

The Germans occupied Czechoslovakia on March 15, 1939, and when war was declared, Stella had to interrupt her medical studies. After a failed attempt to join her sister in England, Stella managed to get an exit visa from the Gestapo and obtained passage on a boat leaving Italy for Shanghai in the spring of 1940. Her parents were supposed to join her, but they could not obtain the necessary papers to emigrate; they told her to go on ahead in hopes that they could follow her.

Stella and Eli continued their studies in Shanghai at the Aurora University Medical School, which was run by French Jesuits. They met in the anatomy lab there, and worked together in the hospital. Elie obtained his medical degree in 1945, and Stella one year later.

During the war, there had been little news of what was happening in the outside world, but after the war, word came to the Stella and Elie. Stella was notified by the Red Cross that her parents had perished in Auschwitz. Elie’s parents had also died in concentration camps.

Stella was one of the first to obtain a visa for the United States after the war. Because of quota restrictions, Elie had to wait until January 1948. They were married that year, and settled in San Francisco where they worked and raised two children. After getting his license, Elie opened a private practice in General Medicine and joined the staff of Mt. Zion Hospital. Stella became the first female intern at the Southern Pacific Hospital, and later worked as a physician for the City of San Francisco.

Gerda Levy

Gerda’s family escaped Europe and spent the war years in Bolivia and Argentina.

Gerda was born in Breslau, Germany, in 1925, the only child of Georg and Gertrud Bielski. Her father, a well-established businessman, had fought for the German army in World War I. He felt that he was a German first and a Jew second, and that he had nothing to worry about.

When Gerda was 13, SS troops burst into the classroom of her Jewish school and murdered the teacher in front of the students. It was to be the last day of Gerda’s formal education. Her parents attempted to get visas to leave Germany, but it was too late. Their funds were confiscated and their situation began to look hopeless.

My father had hidden in a neighbor’s house when the soldiers approached. My mother and I watched as the SS men threw my piano out the window, and then, piece-by-piece, all of our furniture followed. Our home was destroyed.

An aunt in Switzerland sent money, which Gerda’s father used to purchase counterfeit visas and tickets on a ship scheduled to leave Europe; that voyage was cancelled. The next ship on which the family had reservations also cancelled their tickets the night before sailing. They received a telegram saying that ship had burned at sea a few days later. They finally obtained passage on a ship sailing from Genoa. After two days of waiting with neither food nor water, they boarded and were crammed into a cabin with about fifty other people. There was little to eat during the entire voyage, but at last they were leaving Germany.

Upon the family’s arrival in Chile, officials discovered their counterfeit visas, but a Jewish organization arranged for the family to land and continue on to La Paz, Bolivia. When the government announced that too many immigrants were living in La Paz, they had to move to a small village in the interior of the country. There, they opened a primitive hotel and restaurant.

Three years later, Gerda left to move to the city on her own. She met and married a photographer who was twenty years older than she was. They crossed the border illegally into Argentina where Gerda worked in a photography studio and took boarders into their home.

Gerda eventually moved to California where she became a successful businesswoman owning a chain of photography studios.

Gabriella Mautner

Gabriella and her family survived the Holocaust by staying on the move and hiding in Italy, Holland, Belgium, France and Switzerland.

Considering the horror of the past and the painful memory of all those less fortunate than my family, I am forever grateful for the gift of life. Among other things, it taught me never to take anything for granted.

Gabriella Mautner (neé Kramer) was born in 1922 in Chemnitz, Germany where she lived with her parents and older brother Wilhelm. In the spring of 1933, soon after the Nazis came into power, she and her cousin Hannah were called “dirty Jews” by bullies, and made to sweep the street. Her father had read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf, and saw the writing on the wall, so that night the family hastily left for Switzerland by train. They first went to stay with friends in Italy, and then in Holland, joining Gabriella’s uncle to run the family business. However, it was soon confiscated by the Nazis, and the Kramers were ordered to leave the coast.

In January 1942, Gabriella’s family was among the first to be called for deportation. Feigning illness, her father was able to secure a short extension. With much difficulty, the family managed to get to Belgium and hide. After five months in Brussels, Gabriella and her mother were caught in a Gestapo trap, but thanks to false papers and pretending to understand only French, they were released.

They immediately prepared to travel to the still unoccupied south of France and reached a village near Lyon. Unfortunately, the French Vichy regime had begun arresting Jews in the area and turning them over to the Germans.

After two desperate and failed attempts, the family finally reached Switzerland. But, they were shortly arrested and sent to a camp together with hundreds of others. Thanks to friends who vouched for them, they were freed about two months later and took refuge in the nearby mountains.

Gabriella’s brother had immigrated to America in 1938. They had a brief reunion near the end of the war, he as was back in Europe fighting with the 45th Division under General Patton, helping to liberate Dachau.

Gabriella finally immigrated to the United States. She earned a Master’s degree, and is a published author of novels and memoirs. She taught creative writing at San Francisco State University and the Fromm Institute.

Hella and Frank Roubicek

Hella was a passenger on the ill-fated

SS St. Louis ship that was turned back from Cuba and forced to return to

Europe.

Frank survived the Lodz ghetto and several forced labor and

concentration camps.

Hella Roubicek (née Lövinsohn) was born in Frankfurt/Oder, Germany in 1926. where her father worked as a doctor. In 1939, the Gestapo rounded up all the Jewish men in Frankfurt. One of the police officers, a neighbor, pulled her father out of the line-up, probably saving his life. The Gestapo, however, gave him an ultimatum: leave Germany within two months or be taken, like the others, to a concentration camp. It was extremely difficult to find a country of asylum; the only options at that time were Shanghai and Cuba. Hella’s mother managed to find a sponsor and the necessary funds, and six weeks later her father was on his way to Havana. Hella and her mother were waiting for exit permission to join him when, a special one-way trip to Havana was announced by a German cruise line.

The SS St. Louis was scheduled to sail May 13, 1939 with nine hundred thirty-five refugees on board. Hella and her mother were among them. But when the ship anchored outside the Havana harbor, the passengers learned that their entry permits would not be honored.

After agonizing negotiations, the St. Louis was ordered out of Cuban waters and sailed to an area off the Florida coast. The US also denied landing, even though the majority of passengers held affidavits, making them eligible for immigration. The ship was turned back to Europe and the ship’s captain vowed to do everything in his power not to take them back to Germany. Telegrams went to countries all over the world. Finally, England, France, Holland and Belgium granted the waiting passengers asylum.

Frank Roubicek was born in Prague in 1911. He was educated there and worked as an attorney until the Nazis invaded in 1939, the same year that Hella’s town was invaded. In 1941, Frank’s family was deported to the ghetto in Lodz, Poland where living conditions were brutal. The food rations were barely enough to survive, epidemics broke out, and many died as they awaited deportation.

Near collapse, Frank was sent to work in an ammunition factory in Czestochowa. When it was evacuated, Frank was shipped in a crowded cattle car to Buchenwald. He was sent next to Rehmsdorf, where he survived merciless treatment by the guards. As the Allied troops advanced, the camp was evacuated. Those who survived but were unable to walk were shot by the guards. Those remaining were forced on a death march to Theresienstadt, where Frank collapsed.

After Hella’s ill-fated journey, she and her mother went ashore in Belgium five weeks after setting out on their voyage. They managed to obtain visas and were able to immigrate to the US in 1940 before the German invasion. Most of the other passengers who had been on the ship, including Hella’s grandmother and aunt, could not leave Europe in time and were killed by the Nazis.

Frank was liberated in April 1945 by Russian troops. He was the only one of his family who survived. Of the 5,000 Jews from Prague who were sent to Lodz, only about 240 returned after the war. Frank was one of them; he worked in the legal department of the Ministry of Social Welfare in Prague, but escaped to Vienna after the Communist takeover in 1951.

Frank and Hella were married in 1959. They lived and raised a family in Berkeley, California, where Frank owned a business in nutritional supplements and Hella worked as a language teacher.

Bitter war experiences have taught me how to appreciate the basic values of life, and to fully appreciate the good things it has to offer.

Pola Ash

A long and dangerous journey took Pola Ash and her parents from their home in Poland to Russia, Japan, and finally Shanghai.

All stateless people had to move into the Shanghai ghetto. Many of the Polish people formed community groups and tried to help each other. But our life was extremely difficult.

Born in 1927, Pola Ash (née Rosenbaum) lived with her parents in a residential section of Krakow, Poland, where her father sold furs. Two days after the beginning of the Nazi invasion, the Rosenbaums crowded into a small car with another young couple and their baby. They departed for Lublin, driving at night to avoid German strafings.

When Lublin was bombed, the family drove on until they ran out of gas. Pola and her mother rented a room in the town where they stopped. Her father took a train to Wilno, where he had a factory, to arrange for them to stay. When the Russians overtook that city, the family obtained visas for Japan, thanks to Japanese consul Sugihara.

After a three-week journey Pola and her parents arrived in Vladivostok, Russia, where they boarded a ship for Japan. They were sent to Kobe and stayed there about nine months, with Pola attending a Japanese school. But, the family’s passports were stolen when Pola’s father was traveling back from Tokyo, where he had gone to renew them.

Pola’s father was forced to go to the Polish consulate to get new passports — but the consulate had moved to Shanghai, and so the Rosenbaums went there. Soon, Shanghai was also occupied by the Japanese, who forced all stateless people into the ghetto. Pola attended an English school outside the ghetto, but every few weeks she was required to get a new permit. Meanwhile, her father was briefly arrested. While in prison, officials stated that he developed an infection and became extremely ill. Pola, however, believed he was poisoned.

When Shanghai was liberated, Pola and her parents, aided by relatives, obtained visas to immigrate to the United States. She got a scholarship to attend college in New York. Her parents had moved to San Francisco, where they had bought a small clothing store. After finishing her studies, Pola joined them and they worked together in the store and shared a small apartment. Pola remained in California where she married and raised a family.

Erika Meier

Erika Meier and her family left Austria and found refuge in Shanghai, where they survived the Japanese occupation.

Our doorbell rang, and there stood my best friend’s brother in full Nazi uniform. The Boy Scout troop in which he had been active was a disguised Nazi den. It was the first of many disappointments in people I had thought I knew.

Erika Meier was born in 1921 in a small town near Vienna. Her father was an architect and civil engineer and her mother was an opera singer and voice teacher. In March 1938, Hitler annexed Austria, and much of the population became enthusiastic Nazis. Four months later, a group of Nazis burst into Erika’s house in the middle of the night with guns drawn, and ordered the family to leave within 24 hours. They moved to another area of Vienna and kept mostly indoors. Her father’s business was taken over by a Nazi.

Erika’s family wanted to immigrate to the US but the quota for people born in Austria was so small that it would have taken several years before they could hope to obtain a visa – and time was running out fast. No visa was necessary to get to Shanghai, and Erika’s father contacted his cousin already living there. In 1939, holding “stateless” passports marked with “J”, the family crossed the border into Italy where they boarded a ship bound for Shanghai.

For a while, it seemed as though things were going to be all right. However, after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Japanese took over Shanghai and life became very difficult. Japanese troops entered the city and took over all “enemy” businesses. All stateless refugees had to move into a designated area where living conditions were very poor. There were barbed-wire barricades, nightly blackouts and the constant threat of air raids.

An uncle and Erika’s maternal grandmother eventually joined them in Shanghai. But her father’s large extended family had hesitated to leave Austria and all died in concentration camps. While in Shanghai, Erika met her future husband; when the war ended, they made plans to go to Amerika. It took two years for them to get visas, and even longer for Erika’s parents and grandmother to join them. They eventually settled in Northern California, living as was customary in the family with four generations together in one house.

John, Elizabeth, and Renata Polt

The Polt family fled their native Czechoslovakia in 1938, going to Switzerland, Cuba, and then the United States.

For our mother, the wall hanging in our portrait represents the two halves of the family’s experience: first in Europe, and then in Amerika.

The Polt (formerly Pollatschek) family hailed from Aussig, a small industrial city in northern Bohemia where they had lived for generations. Son John was born in 1929 to his father Frederick, a lawyer, and mother, Elizabeth; daughter Renata came in 1932. Life in Aussig seemed stable and predictable. The family had lived in Bohemia for generations and seemed destined to remain there.

Until 1918, the area had been part of the Austrian Empire, and the family spoke German, rather than Czech. But the Nazis coveted the area, which they termed the Sudetenland. By the 1930s, the Nazi-leaning Sudeten German Party began to boycott Jewish stores, persuaded Gentiles to stop patronizing Jewish professionals, and campaigned for a return of the area to the Reich.

Frederick was raised Jewish but had essentially left the faith in his late teens. Elizabeth’s father had been Jewish, but had converted to Christianity on marrying her mother. Elizabeth, John, and Renata were baptized, but nevertheless, the family was considered Jewish in the eyes of the Nazis.

Concerned about the rise of Nazism and alarmed by news of an arms buildup on the Czech border, Frederick and Elizabeth decided to temporarily move the family to Switzerland. On September 11, 1938, they left Aussig; eighteen days later, the Munich Agreement ceded the area to Hitler. But staying in Switzerland was not an option, since the Swiss did not permit foreigners to take jobs nor even to rent apartments.

In 1939, when John was 10 and Renata was 7, the family sailed for Cuba to await American visas. About a year later, the Polts immigrated to Amerika. They lived in New York and Florida before settling in California.

Frederick’s mother had remained in Europe. She was sent to Theresienstadt, and then to Treblinka, where she was killed. Many other family members, as well as Jewish members of Elizabeth’s family, were also murdered by the Nazis.

Both John and Renata continued their education in the United States. John became a professor of Spanish at the University of California, Berkeley. Renata earned a master’s degree and taught English, film history, German, and Jewish Studies. She wrote travel articles, as well as film and theater reviews.

In the Concentration Camps

The Nazis imprisoned and murdered Jews in concentration camps located in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. There were three different kinds of camps: transit, labor, and extermination. Many prisoners in concentration camps died within months of arriving from violence, starvation, or being worked to death. Others perished on Death Marches: forced, long-distance marches during which already sick and starving prisoners were shot or left behind for dead if they could not keep up.

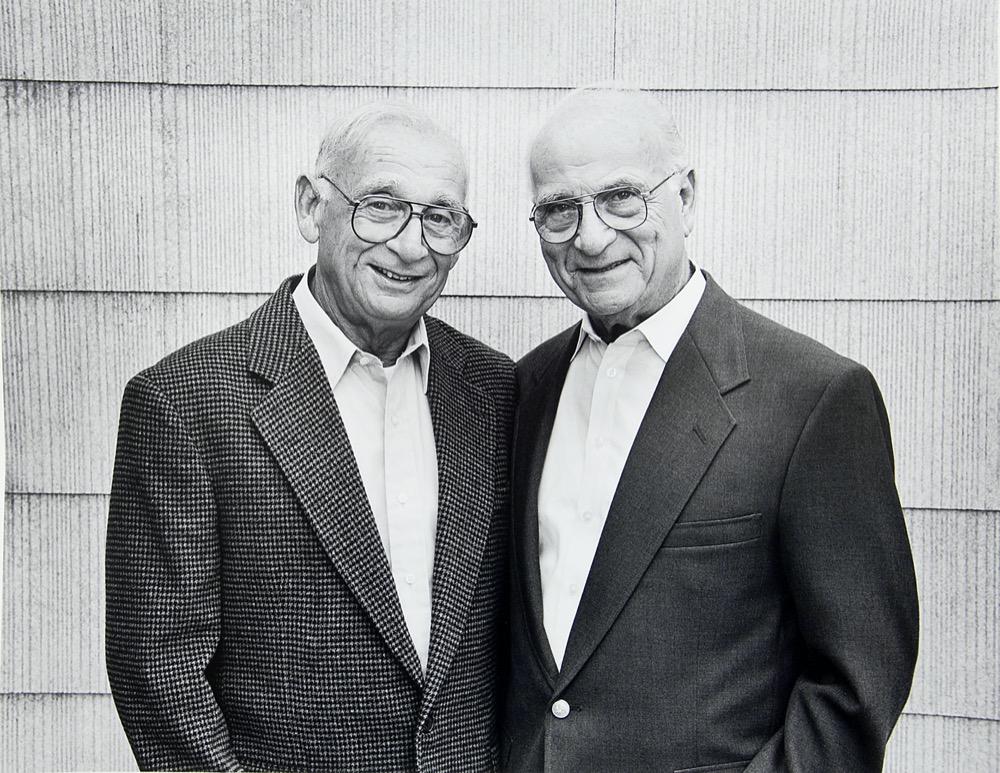

Ernie and Erwin Levy

Brothers Ernest and Erwin Levy were both imprisoned in Auschwitz and other camps. Neither knew the other had survived until after the war.

Beginning in 1934, I was the only Jewish boy in my class and it became impossible for me to study. My teacher was an active Nazi and I was beaten and kicked on a daily basis.

The Levy brothers were born in the small German town of Waldbreitbach (Erwin in 1921 and Ernest in 1925). Their parents were well-educated and, for several generations, the family made a good living as cattle dealers.

In 1938 – one week before Kristallnacht – the family moved to the large city of Cologne. In 1941, the family was sent to the ghetto in Lodz, Poland, but shortly after arriving, they were all separated.

Ernest was taken in a cattle car to Auschwitz. From there, he was sent to Dachau to perform heavy labor, unloading railroad cars digging ditches and building railroad tracks. Just before the liberation of Dachau, Ernest and all the other prisoners who were still able to walk were sent on a Death March into the Alps to be traded for German prisoners of war. Only a handful managed to survive.

Erwin was sent to Posen, and then to Auschwitz; there, he worked as a mechanic and labored in the coal mines. Near starvation, he stole oats from the horses to have some food to eat. Like his brother Ernest, Erwin was sent on a death march, but was liberated by the American Army a week before the war ended.

The brothers had been separated all during the war, and each feared that the other had died. They had a joyous reunion when Erwin traveled to a hospital in Cologne for returning deportees and found Ernest there recovering from typhoid fever. Their parents did not survive and their sister Ruth had disappeared without a trace.

Ernest and Erwin both immigrated to the United States, eventually settling in California. Each man married, continued their education, worked, and created their own businesses.

Once they were reunited, the two brothers remained close for the rest of their lives.

Irving Zale

Irving Zale endured the horrors of the infamous Plaszow concentration camp which was chronicled in the film Schindler’s List.

Irving Zale (né Zahler), was born in 1926 in Cologne, Germany. The family had moved from Poland to seek improved economic conditions, but young Irving was ostracized by his German classmates and eventually transferred to a Jewish junior high school. Irving’s father was active in the short-lived Polish-German Friendship Society, and Poland’s Consul General warned him of the impending Nazi roundup of all Polish Jews living in Germany. The family lacked the money to purchase a passport to another country, so their only alternative was to pack up their possessions and return to Krakow where Irving’s relatives lived.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Irving’s parents attempted to flee further east but were overtaken by German troops and forced to return to Krakow. The family remained in Krakow until 1943 when they were sent to the Plaszow concentration camp, which was turned into a killing field.

The camp commandant Amon Goeth was a sadist who enjoyed killing for sport. Since there was no rule against shooting games, any inmate could be ‘kicked off’ by a bullet. On his way to our worksite, Goeth proved his power by shooting ‘five goals’ (five people’s heads).

After enduring months of backbreaking work and inhumane treatment in Plaszow, Irving was transferred to the HASAG Labor Camp in Czenstochowa, Poland which produced war material for the Wehrmacht under civilian and military supervision. Living conditions were more tolerable, and Irving was out of the reach of the dreaded SS Officers. The camp was liberated by the Red Army in January 1945.

Irving returned to Krakow, where he found some relatives who had survived by hiding with a Polish family. His parents had been transferred from Plaszow to extermination camps, where they died.

An uncle, who had left Poland three days before the start of the war to visit the New York World’s Fair, helped Irving to immigrate to the US. Irving became a US citizen and served in the US Army. He worked as an accountant, married and had two children, and eventually settled in California.

Regina Oppenheimer

Regina Oppenheimer survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen.

Regina Oppenheimer was born in 1922, in the village of Krasnovce, Czechoslovakia. Her mother died when Regina was two-and-a-half years old, and after a year, her father remarried. Because he traveled a great deal, Regina was left with her stepmother, who treated Regina and her brothers very cruelly. When she was twelve, her father died and her brothers left for Palestine. Regina was alone. In 1930, she was sent to live in a children’s home in Prague; she remained there until she was twenty.

The Germans marched into Prague in March 1939 and Regina remembered seeing soldiers everywhere. She was sent to Theresienstadt, where she lived in a room with 42 other women and worked in the fields outside the ghetto.

After two years, Regina and a group of others were jammed into cattle cars. They were in Auschwitz. The Nazis divided the old people from young ones: the smell of burning hair and bones was everywhere and Regina was sure that they would all be selected to die when they had to march naked before German soldiers.

Regina remained in Auschwitz for six months, until she was put on a transport with young people to work in a bomb factory near Berlin. Soon afterwards, they were sent on a six-week death march in the snow to Bergen-Belsen. She had never seen so many dead people as there were at Bergen-Belsen. Weak and hungry, Regina contracted typhus and wondered how long it would take until she was the next to die.

On April 14, 1945, the prisoners were kept awake by constant bombing. The next morning, they got up as usual and lined up outside in formation to be counted. But after many hours, no Germans appeared. They realized they were free.

After liberation, Regina recuperated in a hospital in Sweden. She was sponsored by relatives in the United States and eventually settled in San Francisco, where she married a fellow survivor who had lost his family in the camps. Joining many others, they bought a chicken farm in rural Petaluma where they raised a family.

During the day it is out of my mind, but at night it comes back to me in dreams. I see everything, and I say to myself in these dreams, ‘This time I am smarter. This time I will not go through it. This time I will hide.’

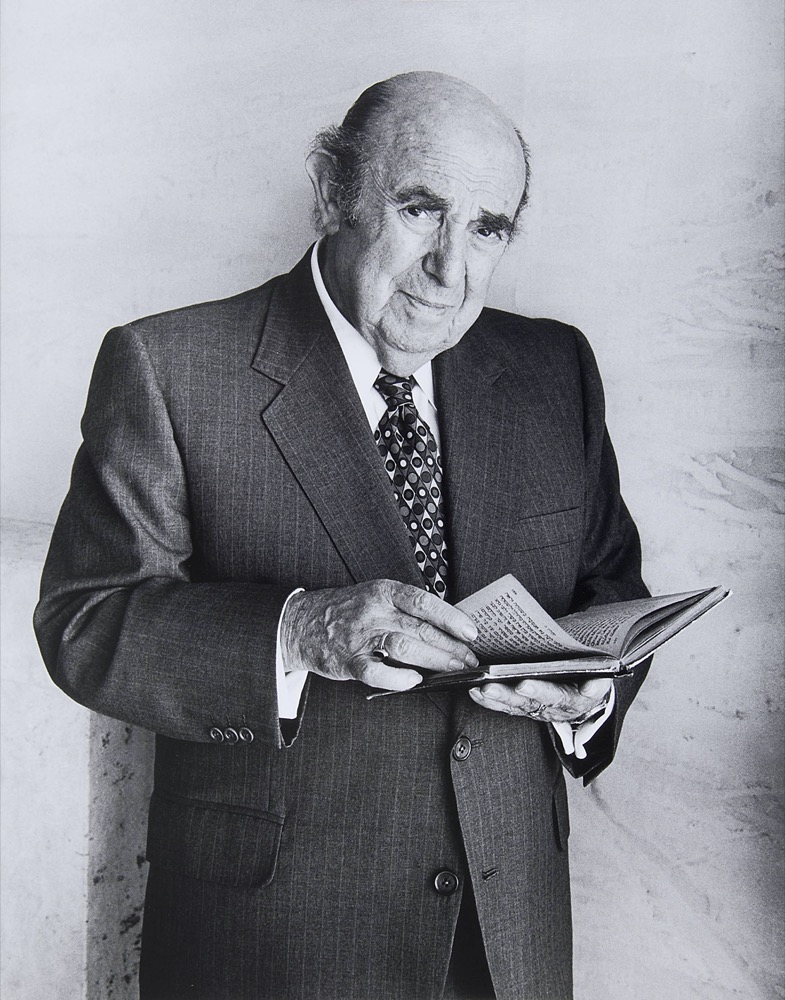

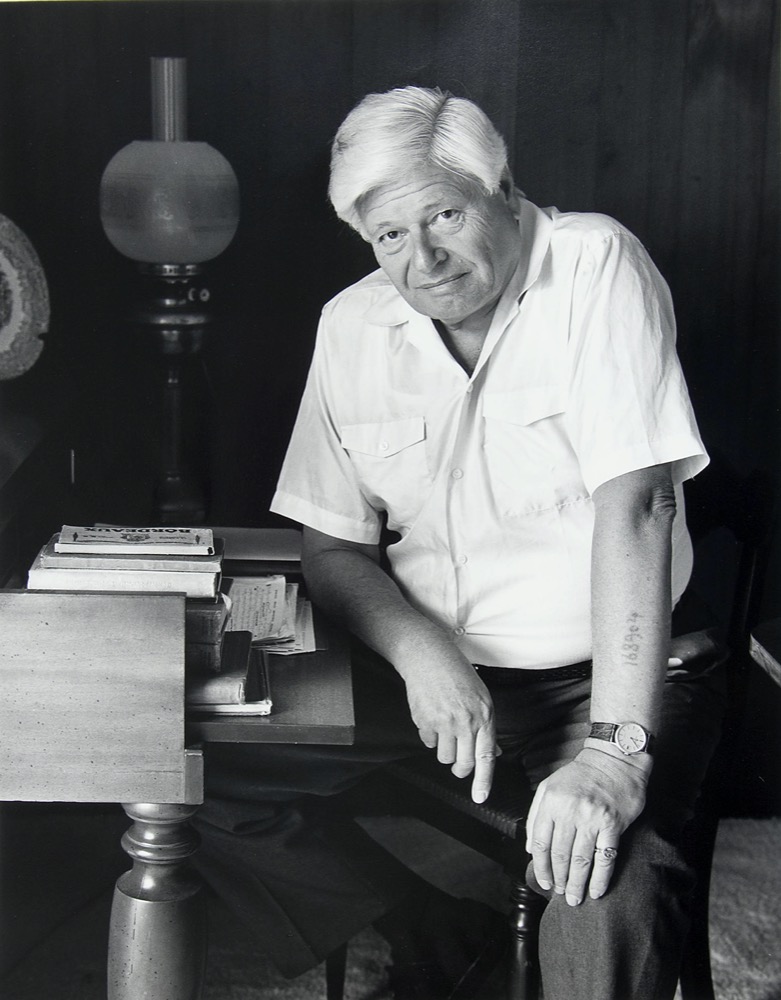

William J. Lowenberg

William Lowenberg survived Auschwitz-Birkenau and Dachau.

William Lowenberg was born in 1926, in Westphalia, Germany, where he lived with his parents and sister Erika. His family’s ancestors had lived in Germany since the 1400s, working as merchants and cattle dealers.

In 1936, the family fled to be near relatives in Holland – what they hoped would be a safe haven from the Nazis. Instead, they were arrested there in 1942 with the rest of the Jewish community and sent to the transit camp Westerbork where they remained for several months. From there, William was separated from his parents and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. No one else from the transport he was on survived the war. His parents and sister were deported to Auschwitz a few weeks after William and were murdered in the gas chambers there.

William remained in Auschwitz-Birkenau until the spring of 1943 when he was sent, along with 300 other men, to Warsaw to demolish the ghetto and to dispose of the bodies of the Jews murdered there. In 1944, the ghetto was liquidated. Out of 12,000 people, there were 3,600 Jews left; of these, only 240 survived the brutal Death March to Dachau. William remained in Dachau until April 30, 1945, when he was liberated by the U.S. Army.

I don’t know what kept me going. The past was gone. There was no future. I wanted to live so badly, and be able to go back and tell my story.

William returned to Holland hoping in vain that some of his family had survived, but in 1949, he immigrated to the United States where he enlisted in the Army and served in the Korean War. He settled in San Francisco where became a prominent member of the real estate business, establishing the Lowenberg Corp, a major industrial real estate firm.

William married and raised a family and was very active in the Jewish community. He served as President of the Jewish Community Federation , President of the Jewish Home for the Aged and the Bureau of Jewish Education. He served on the Board of Governors of the Jewish Agency for Israel and was appointed by President Reagan to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Council, later becoming the Vice Chairman of the Museum.

The book William is holding in his portrait, a section of the Torah, belonged to his father. It was kept by Catholic neighbors and returned to him after the war.

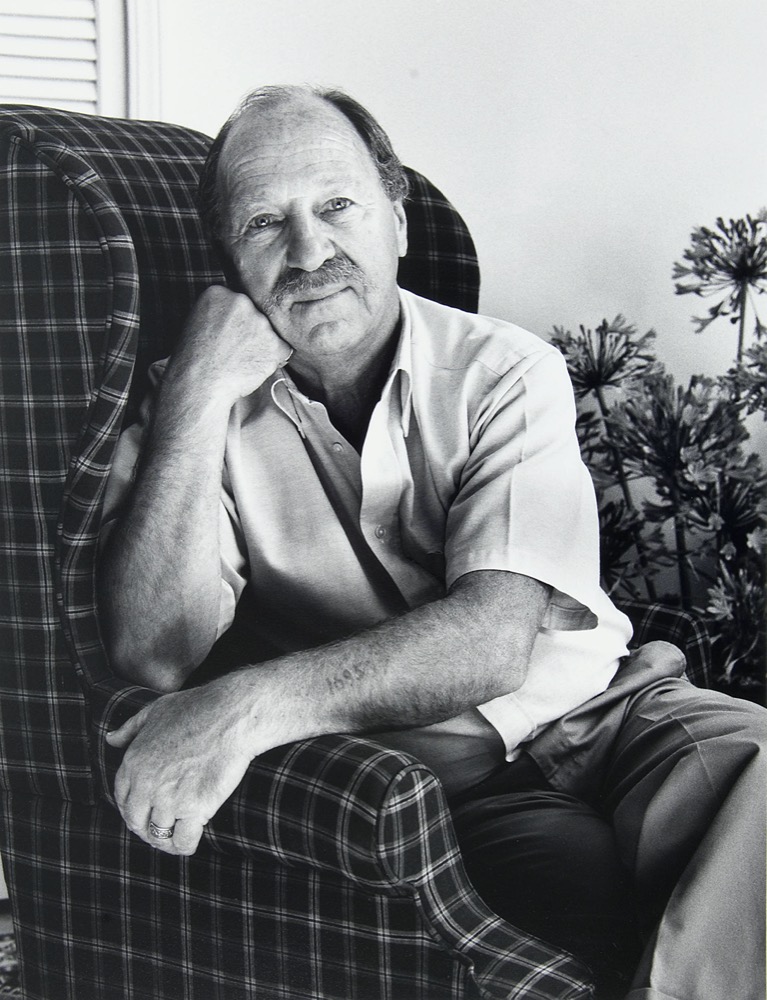

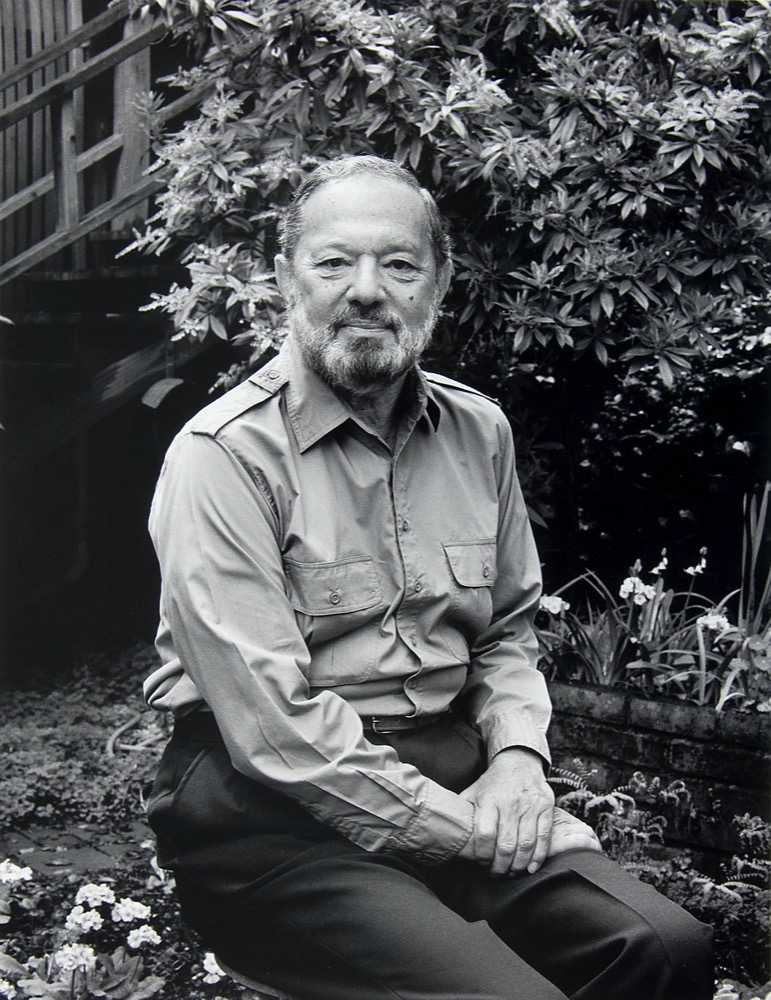

Bernard Offen

Bernard Offen survived the Plaszow, Mauthausen, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Dachau concentration camps.

Bernard Offen was born in 1929 in Krakow-Podgurze, Poland. He lived with his shoemaker father, mother, two brothers, and a sister in the part of the city which was transformed into a ghetto during the Nazi occupation.

When the ghetto was liquidated in 1943, Bernard was sent to the Plaszow slave labor camp, from which he escaped. During his few days of freedom he hid in an old cemetery. He was then smuggled into the Julag I camp near Plaszow, where he hid by taking on the identity of another inmate who had been killed. The Julag camps were absorbed into the Plaszow camp, which had become a concentration camp shortly after the liquidation of the ghetto. In this camp, he was reunited with his father, with whom he worked making boots.

In 1944, 15-year-old Bernard, his father, and two brothers were deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. His brothers remained there, but Bernard and his father were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where, on arrival, they were separated for the last time.

Bernard spent three months in the quarantine barracks at Birkenau. Then, because of the advance of Soviet-Allied forces, he was sent to the Dachau-Landsberg concentration camp. He was liberated by American Allied troops following a death march from the camp in late 1944.

After the war, Bernard searched for other relatives. Although their stories are unknown, it’s likely that Bernard’s mother and sister were deported from the ghetto to Belzec, where they were murdered. In the end, out of fifty-nine members of the family, only Bernard and his two brothers had survived. Bernard found them serving with the Polish Army in Italy, and the three went to England and before migrating to California.

Bernard dedicated himself to telling his personal memories of the Nazi treatment of Jews and has created documentary films and written about his wartime experiences. In 1981, he went to Poland for the first time since the war and has returned each year, guiding thousands of people to the sites of former ghettos and of the Plaszow and Auschwitz-Birkenau camps.

I decided to push beyond my personal discomfort and pain by sharing what happened in Auschwitz. I spend each summer in Poland in order to create a deeper level of understanding of what happened there.

Helen and Joe Farkas

Helen was sent first to a ghetto, then to several concentration camps, and finally forced on a death march. Her husband, Joe, survived a forced labor camp.

Our struggle to survive was not just from day to day, but from hour to hour, minute to minute.

Helen Farkas (née Safar) was born in 1920 in Satu-Mare, Romania, which became part of Hungary in 1940. She lived there with her parents and eight siblings until May 1944, when they were arrested and deported to Auschwitz. The Nazis immediately separated 24-year-old Helen and her sisters from the rest of their family, and sent them to do forced labor. Most of the older adults, as well as the younger children, were sent straight to the gas chambers. From Auschwitz, Helen was sent to Silesia, where, with 2,000 others, she was sent on a death march to Bergen-Belsen. Those who could not march were shot to death and left unburied along the way. After enduring desperate conditions, months of starving and freezing, less than one hundred survived. One very cold night, Helen and her sister Ethel escaped from Bergen-Belsen. They remained hidden for about two weeks, until the war ended.

Joe Farkas, also born in Satu-Mare, Romania, lived there with his parents and five siblings. As a child, he was obsessed with soccer and was an excellent player. During the war, he was placed in a forced labor camp, where he had the chance to play soccer and worked as a cook for the battalion. This kept him from being sent to the front lines, where many Jewish men were used as human mine detectors or died of starvation and beatings. Joe was liberated after the arrival of the Russian troops in 1944. He walked two hundred miles to get home to Satu-Mare.

Joe and Helen had been engaged before the war. They were reunited in Satu-Mare and married in August 1945.

Both Helen and Joe survived the Nazis’ atrocities, but remained prisoners in the area’s Communist regime. They escaped in 1948. It was very hazardous and many people who tried to cross the border were shot, yet they preferred to risk their lives rather than live as prisoners in their own home town.

After reaching Austria, the couple lived in a Displaced Persons camp. They immigrated to the United States eight months later, where Joe was recruited by a Hungarian/American soccer team. They eventually moved to California, where they worked with other relatives in family-owned shoe stores and started their family.

Helen lost many family members including her parents, two brothers and a sister. Joe’s parents died in Auschwitz. His brothers and sisters survived the camps. Helen often spoke to school students and other groups about her wartime experiences. With her daughter’s help, she wrote a book “Remember the Holocaust.”

Roma Barnes

Roma Barnes survived several slave labor camps. Her parents and brother were killed in Sobibor.

Roma Barnes (née Rozenman) was born in Demblin, Poland in 1930. Roma’s father’s family owned a sawmill in the town, and she had a happy childhood with a large extended family nearby. When the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Roma and her family hid in the nearby forest. When they returned to the town it was occupied.

Roma believed that her family was not as immediately impacted by the occupation because their sawmill was half-owned by a Pole. But, during Passover in 1942, all of the Jews in the town were rounded up in the town square. Her mother told her, “Run! You have to survive!” Roma hid in a Polish farmer’s outhouse, and when she returned to the town, her family was gone.

I came back to the town. I saw friends, people I knew, dead…the doorways, the well, blood was streaming out. My parents and brother were gone…I was alone.

Roma’s survival depended on not looking Jewish and not having an accent when she spoke Polish. She escaped many roundups but eventually was captured with some of her relatives. Roma was sent first to a labor camp, where she worked with other young people in the fields. Roma was transferred to other camps, and remembered how the Germans took some of the children and threw them into a hole they had dug and then threw grenades in. At Camp Hasag, an ammunitions factory, she worked making shells until the Russians liberated her in January 1945. Roma was 14.

The Jewish Refugee Committee was responsible for children who survived the war. They placed Roma in an orphanage in Lodz, Poland and sent her to Czechoslovakia, then to Scotland, and finally to England, where she went to school and worked for seven years. There, she met and married an American, eventually moving to California and raising a family.

Eventually, Roma learned that, along with 2000 Jews from her town, her parents and brother had been taken to the death camp Sobibor in one of the first transports and were all gassed. Of her large extended family, only a few aunts and cousins were alive after the war.

The Menorah in her portrait has been in Roma’s family for 300 years. Buried for protection, it was uncovered after the war by her Aunt Eva.

Karel Langer

Karel Langer survived several concentration camps.

Karel Langer was born in 1929 in Uhersky Brod, a small rural town in Czechoslovakia. He enjoyed playing in the family’s lumberyard and going hunting with his older brother Pavel and his father.

Evicted from their home in 1939 when the Germans invaded, the family was moved into the Jewish section of the town, living with curfews and restrictions. In January 1943, 14-year-old Karel and his family were assembled at the local high school and sent by train to Theresienstadt, the Nazis’ “model” concentration camp.

That December, the family was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and housed in the so-called Familienlager (family camp). Located very close to the gas chambers and crematoria, the stench of burning bodies surrounded them. They lived from day to day, not knowing what fate awaited them.

In 1944, the entire family was again sent on, this time to work camps in Germany. Karel, his father, and his brother went to Blechhammer, where he witnessed the execution by hanging of eight innocent prisoners. His mother went to Hamburg as a part of a work brigade, cleaning the streets after the Allied air attacks.

Despite the personal danger, I remember being very happy when the Allies bombed the factory where we were working. To us this meant we were getting closer to the end of the war and closer to freedom.

In January 1945, a Russian offensive came within a few miles of Blechhammer. The Germans evacuated the camp and forced the inmates on a two-week death march during which Karel’s father died. Karel was placed in the camp hospital with frozen feet, which he had developed when his shoes fell off on the march through the snow.

In April 1945, the camp was liberated by the American Army. Karel, his mother, and his brother were repatriated to Czechoslovakia, and eventually found their way back home. Approximately 20 survivors returned to the town, which had a pre-war population of ~900 Jews.

After the war, Karel went first to England to school and then in 1949 to Israel to join his mother and brother. He moved to Canada and in 1961 to San Francisco where he married and started a retail furniture company called The Chair Store.

Leah Laskowski

Leah Laskowski survived the Lodz ghetto, Auschwitz, Stutthof, and a death march.

Leah Laskowski (née Russ) was born in 1912 in Warta, Poland, one of seven siblings. The family moved to Lodz in the mid-1930s, and when the war broke out, they were sent to the ghetto there.

In June 1944, 32-year-old Leah, her mother, and her two sisters were herded into cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. SS guards ordered the prisoners to make two columns. Leah and her two sisters were directed to the right. Their mother, in the left column, was sent to the gas chambers. Leah remembered hearing her mother scream “Don’t run after me. You are still young. Live. Live. Save yourselves”

After being stripped and having her head shaved, Leah and her sisters were given coarse rags to wear and marched barefooted to barracks. Eventually, Leah was sent to Stutthof concentration camp where the conditions were brutal and where, just for fun, the officers would beat them. Almost a thousand women occupied each barrack, sleeping on wooden planks. They had no sanitary facilities and their clothes were full of lice. Every day hundreds died of starvation and typhoid.

We had to be counted in the yard every morning no matter how we felt, no matter what the weather, rain or cold or snow or wind. Sometimes the count lasted for hours until they got it right. It could never be right because some of us had already died.

In March 1945, the surviving prisoners were marched out. They walked for days, many dying from starvation and exhaustion. They were locked in barns at night, sleeping on wet straw and at one place, a Nazi guard knocked Leah down, leaving her for dead.

When Leah returned to Lodz after the war, she learned that that the rest of her family had been killed. She then went to Warta, where she married Michael Laskowski. He, with the help of a teenaged Polish neighbor named Dominik Michalak, had escaped the Nazi roundup, and hidden underground for more than four years. Leah, Michael and their daughter Miriam immigrated to the United States in 1950. She chose to be photographed with a pillow she made in a German Displaced Persons camp after the war, and a quilt she created years later in California.

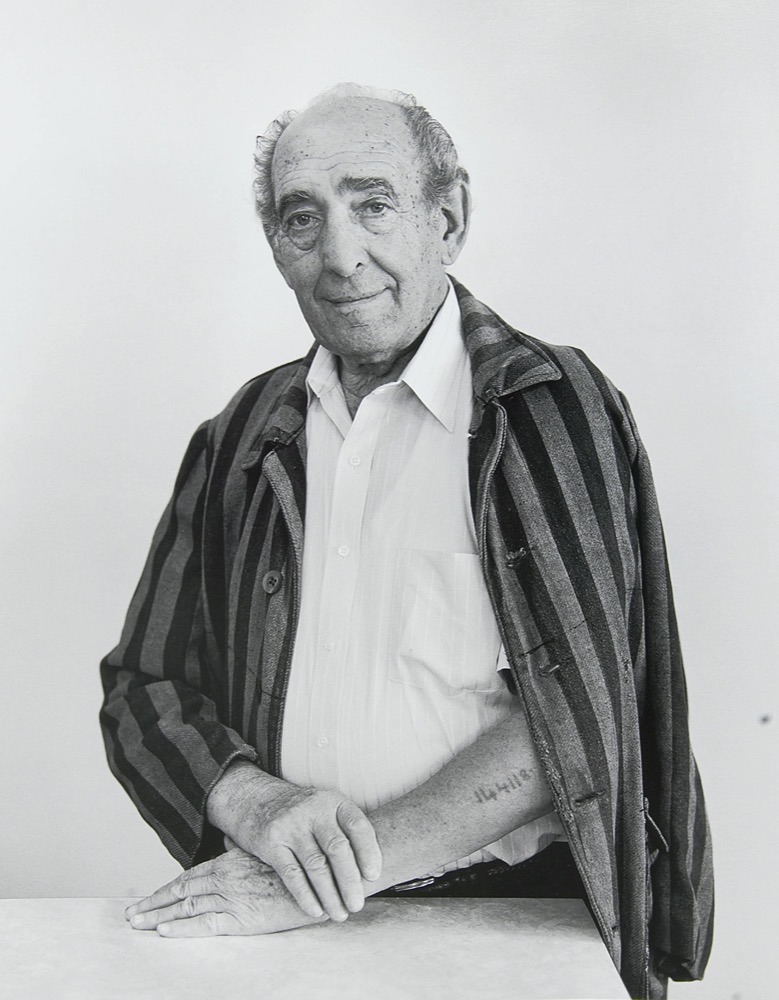

Sam Reselbach

Sam Reselbach worked as a slave laborer at camps in Nazi Germany and occupied Poland. He was the only one of seven children in the family to survive.

In my portrait I am wearing the jacket I wore in Auschwitz. It was my shield. I put a cement bag under the coat so the water would not seep through. When we were liberated, I kept the coat.

Sam Reselbach was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1919. His father was a painting contractor, and Sam began working as a painter when he was fourteen. In 1941, Sam’s family was sent to the Lodz Ghetto, but the Nazis quickly assigned 22-year-old Sam to work camps. There, he did heavy labor, dragging tree stumps and heavy sacks of cement to build a highway.

Next, he and ~2,000 other men were transported in cattle cars to a labor camp near Berlin, where they procued munitions. It was dangerous work with heavy machinery, and the graphite emitted during the process tore up Sam’s lungs.

In September 1943, all of the men working in the factory were deported to Birkenau. The train journey in a cattle car lasted five days. Of the original 2,000, only 205 remained. Upon arrival, they were undressed and their belongings were taken away. They were all supposed to be gassed, but at the last minute they were spared. Sam was tattooed with the numeral 144118.

At the end of 1944, he was evacuated from the Buna camp and forced to march over 20 miles, all at night and in the snow. After another transport to Camp Dora, deep in Germany, he worked in the tunnels in which the V1 and V2 rockets were produced. Finally, Sam was sent to Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated by the British Army.

After the war, Sam remained in Germany, where he met and married a Theresienstadt survivor. They immigrated to the U.S., living in California where Sam worked as a painting contractor. When his first wife died, Sam married a longtime friend who was also a Holocaust survivor.

All the other members of Sam’s large family were gassed in Auschwitz. The names of his parents, Abraham and Sarah; his brothers, Schelomo and Pesach; and his sisters, Rifka, Anna, Tauba, and Luba; are all engraved on a tombstone in California.

Mella Wendel

Mella Wendel survived the camps at Maidane, Malchow, and Auschwitz-Birkenau, as well as a Death March to Ravensbrück.

I went through several selections completely naked. My life was always hanging on a thin line. But God saved me from all these terrible experiences and I survived.

Mella Wendel Katznelson (née Schwietzer ) was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1926, the youngest of six brothers and three sisters. During the war, the family attempted to remain together, but this became impossible.

Mella was sent first to Maidanek, and then to Auschwitz-Birkenau. She worked carrying heavy wooden pallets of fertilizer and gravel back and forth, exposed to the winter cold and summer heat, wearing only wooden shoes and a striped uniform. She believed that the Germans worked the prisoners so hard so that they would die and be put into the crematoriums.

Mella endured many terrible experiences in the camps. She was severely beaten by the Germans even for minor offenses, such as not walking straight. One day, she was exhausted and remained in her block instead of going to work. An older officer caught her. Miraculously, he spared her life; instead of shooting her, he slapped her and let her go.

In 1943, when Mella was in Birkenau, she was chosen for labor in the UNION factory where she inspected ammunition. Because she now worked inside a building, she was warm and survived even with only limited rations food: a small portion of bread and watered-down soup made out of weeds.

In the winter of 1945, the Russians bombed Auschwitz and the prisoners were sent on a death march to Ravensbrück. On this march, Mella’s feet were badly frostbitten, and she almost lost her toes.

Mella was liberated by the English army in Hamburg, Germany in May 1945. Mella’s oldest brother David had escaped from Poland to Russia in 1939 and immigrated to Israel after the war. He and Mella were the only members of their large family to survive. All the others had been deported and were killed.

Mella married in Germany and moved to Israel with her husband and two children, eventually settling in California. Mella spoke Polish, Yiddish, Russian, English and Hebrew.

John Steiner

John Steiner survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, and the slave labor camps Blechhammer and Reichenbach.

John Steiner was born in Prague in 1925. His university-educated mother translated Gone with the Wind into German, while his father was employed by the leading private bank in the city. Expelled from his school when he was fifteen because of his “racial” background, John transferred to a Jewish technical school.

The entire family actively resisted the Nazis. John’s mother was interrogated in the Gestapo headquarters in the bank building in which his father had worked. John’s father was sent to Theresienstadt in September 1941. John was sent there in August 1942, in retaliation for the assassination of Nazi security chief Reinhard Heydrich. In November of that year, his mother was also deported.

John was later sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, as were his parents. His mother was gassed there, and John and his father were sent to the slave labor camp Blechhammer. He resisted his tormenters by keeping up the will to survive, although losing the belief that he actually would.

Most of my relatives and friends perished in death camps. I survived but lost my previous capacity for love and happiness.

John’s father was liberated from Blechhammer in February 1945. Just one month earlier, John had been sent on a death march to the slave labor camp Reichenbach. From there, he and hundreds of other prisoners were shipped to Dachau in open cattle wagons.

Only a few – the physically strongest – were still alive after their brutal journey. At the age of 20, John became the spokesman for the small group of survivors, courageously addressing the the SS captain and telling him that he should either shoot them or help them. The captain decided on the latter, and ordered special rations for the group for two weeks.

When John was liberated in April 1945, he was near death. He had suffered severe frostbite and the amputation of the toes of his right foot.

After recovering, he returned to Prague and was reunited with his father. John worked for the government, but because of his work against the Communist regime, he had to leave Czechoslovakia. He went to Australia and then the US where he continued his studies and earned a PhD. John taught at the University of California Berkeley and Sonoma State University, where he founded and directed the Holocaust Studies Center. He authored several books on the Holocaust and entered into a dialogue with former perpetrators resulting in major research on the subject.

Clara Hilt

Clara was sent to the Plaszow concentration camp, then to slave labor in Germany, and Theresienstadt.

Clara Hilt (née Hubel) was born in 1915 in Drohobycz, Poland. In 1936, she was living by the Baltic Sea with her husband whom she had recently married, when an order came that women had to leave the city. Her husband was arrested and she never saw him again.

Clara stayed in Krakow with her mother and sister to help in the family grocery store, while her father, brother, and another sister headed east with the retreating Polish army. With food shortages and Polish anti-Semitism, life for the women became increasingly difficult. Finally, they moved to Wolbrom, where they rented a room. Clara secretly gave lessons to Jewish children who were not allowed to attend school, and was paid in desperately needed food.

When the Germans decided to “cleanse” the town of all its Jewish citizens, Clara was sent to the Plaszow camp (the setting of the movie Schindler’s List).

Clara remained at Plaszow for close to two years, until she and 350 other women were sent to a factory in Germany to make guns for the Nazis. When the Germans finally retreated, the prisoners were put on a train to Theresienstadt, where they were liberated. After being hospitalized, Clara went back to Poland to search for her family. She found out that her parents had died in the camps, and her older sister had died on a Death March in the last month of the war. Only a brother and younger sister had survived.

The anti-Semitism of the Poles persuaded Clara and a friend to escape to the free zone and eventually go to Prague. After the war, Clara was reunited with a man named Edward Hilt, who had helped her in the camp. They married and lived in Germany where their son was born, finally immigrating to the United States in 1950.

Clara never got official word that her first husband had died. A single letter from him had been smuggled from the camp in which he was held and sent to Clara. It was Clara’s nightmare that she contributed to his death when he took the risk to send her that letter.

I smile but I do not laugh. My son was raised in a home where laughing was a crime. There are days when I wonder what I am doing here.

A Life in Hiding

During the war, some Jews used false identity papers, were hidden by neighbors, or otherwise disguised their true identity. While some Jews survived the war in hiding, for others, it only postponed deportation or death. Below, you will hear from survivors themselves about their varied experiences.

Andre Gabany

After surviving most of the war with false identity papers, Andre Gabany was imprisoned by Nazi sympathizers.

Andre Gabany was born in Debrecen, Hungary in 1930, into a family that included judges, physicians, and business people. At the beginning of the war, Andre’s father and grandfather had been considered “exempt Jews’ because his grandfather was a respected judge. Andre’s father was even inducted into the Hungarian army as a motorcycle messenger.

Andre, his mother, and grandfather lived in Budapest. They moved to Sopron to be close to an uncle who had been educated in Germany. They hoped this connection would help them receive better treatment, but things did not turn out that way. In Sopron, forced to wear the Star of David, Andre was spat upon and beaten by his classmates for being Jewish. The Gestapo took hostages and forced most of the Jewish population into ghettos, and his uncle was deported to Auschwitz. Relatives helped his mother to obtain false identity papers, and a Christian neighbor helped them escape from the Sopron ghetto back to Budapest. From there, they traveled to a small village next to Lake Balaton, pretending to be refugees fleeing from the Russian occupation.

An officer asked me to identify the good and the bad Hungarians, so that he could have the Nazis sympathizers executed. I had absolute power at age fifteen and I had not one person killed.

As the Russian army was approaching, Hungarian Nazis patrolled the area and discovered that the Gabanys were Jews. They were beaten and arrested. While they were being transported westward to Germany, they were liberated by the Russian army.

In prison, Andre met a high-ranking Russian officer. After the liberation, he asked Andre to identify the good and the bad Hungarians, so that he could have the Nazi sympathizers executed. Andre refused to do so.

Andre, together with his mother, came to America in 1948. He attended the University of California and Stanford University. Andre worked as a mechanical engineer and participated in major engineering projects including the first American space satellite and the design and construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System. He and his wife Solange, who was born in Casablanca, Morocco raised their family in California.

Of his large extended family, only Andre, his mother, and his grandfather survived the Holocaust. His father had been driven out to a minefield by the Nazis and killed. Most of his schoolmates were deported and died.

Elizabeth Pschorr

Elizabeth Pschorr was married to an Aryan and survived the war in Germany because of this “Privileged Marriage.”

Elizabeth Pschorr (née Holzer) was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1911. Her mother was a German gentile and her father was an Austrian Jew. Her father felt German first, and Jewish second, and, wishing to save the family from persecution, had the children baptized as Lutheran. Thus, as a child Elizabeth was unaware of her Jewish ancestry. Her first encounter with anti-Semitism occurred when she was about eight years old; her best school friend told her that she could not play with her anymore because she was Jewish.

In 1933, the Nazi party came to power. Elizabeth and her Aryan fiancé, Fritz Georg Pschorr, agreed that their love was stronger than racial politics. Although his family did not approve of his marriage to Elizabeth, the couple decided to remain in Germany and found refuge at the Pschorr family property near Munich, where they tried to live as inconspicuously as possible. Their three children, when born, were baptized. Under the Nuremberg laws, their marriage and the fact that they had children protected Elizabeth to a certain degree. However, she still had to surrender her German passport and carry an identity card stamped with the “J” and the name “Sarah.”

We escaped the destruction of Hamburg by moving to the country and also avoided my registration at the Jewish Center. This was a required act all over Germany and served later for tracing Jews for deportation.

Elizabeth was threatened by local party leaders, who confiscated money and rations. She was desperate and had to find food and medical supplies for the family by begging the neighboring farmers. Elizabeth’s husband was drafted into the army and had to disclose his wife’s identity. He was enlisted in the Organization Todt to do heavy labor, but he fell ill with hepatitis and did not have to serve in the end.

Aided by the organization Joint, the family spent time in a displaced persons camp until they were able to leave for America on a troop transport. Elizabeth wrote a book, A Privileged Marriage, and often spoke to groups describing her wartime experiences.

Louis de Groot

Louis de Groot spent the war hiding in many different cities and with different people in the Netherlands. He was the only one of his immediate family to survive.

Louis de Groot was born in June 1929 in Amersfoort, the Netherlands. He lived with his parents, and his sister Rachel in a spacious apartment above their electrical store in Arnem. On November 16, 1942, a local policeman came into the store; the policeman shared his suspicion that the Germans were planning a roundup of Jews that evening.

The family took the policeman’s warning seriously. They separated, and each went into hiding in a different location. Louis’ parents reminded him that people were risking their lives by opening their home to him. His sister’s last words to the 13-year-old Louis were, “Be strong.”

Because of changing conditions that threatened his safety and increased the risk of discovery, Louis moved thirteen times within the next year. He was helped by a Christian couple, Anne and Dirk Onderweegs and their daughter Bonnette, in whose home he arrived in January 1944.

I am the sole beneficiary of my parents’ brave decision for the family to go into hiding. Every day I thank them for having had the courage to take that step while there were so many unknowns to deal with. They are my heroes.

Louis’ parents went to Amsterdam, a few blocks from where Anne Frank and her family were hiding. In 1944, his parents and sister were denounced and arrested by collaborating Dutch policemen. They were deported to Auschwitz where they were killed.

The Oderweegs treated Louis like their son, and he continued living with them for 16 months after the liberation. In 1946, wishing to return to a Jewish environment, Louis moved to the Jewish Boys’ Orphanage in Amsterdam.

In 1948, Louis volunteered for service in the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organization for the founding of the new state of Israel. The following year he returned to Holland and finished high school. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1950, and the following year was inducted into the U.S. Army during the Korean conflict. Louis earned a master’s degree in economics at Columbia University and worked as a business economist with the IBM Corporation. In the U.S., he met his wife Barbara, an artist, who helped him live with his painful wartime losses and to build a family.

Marianne Gerhart

The daughter of a German Jewish mother and a non-Jewish father, Marianne Gerhart lived through the war in Germany.

I am often asked, sometimes with barely disguised suspicion, ‘If you and your Jewish mother lived in Germany during the Nazi time, how come you survived?’ We survived because at critical moments there always appeared in our lives people who were willing to take great personal risks on our behalf.

Marianne Gerhart (née Zeise) was born in Germany in 1923. Her Christian father had been decorated with the Iron Cross, but because of his marriage to a Jewish woman, he lost his position as a psychologist. In 1939, he moved to Berlin to train at the Jung Institute, but as protection for the family, he periodically returned so that the neighbors could see that Marianne’s mother was still married to an “Aryan.” Marianne’s mother, a well-known actress, lost her job but continued to give private drama lessons. One of her students later confided that the Nazis had assigned him to spy on her.

When nine-year-old Marianne attracted attention at school for not a wearing Hitler Youth uniforms at school, her father found a Lutheran school that was willing to accept her. Being half-Jewish, Marianne was able to finish high school, but was barred from the University and from employment. Nazi headquarters assigned her to a night job washing streetcars, but she felt increasingly vulnerable in a place where workers could be easily rounded up.

After making an anti-Nazi remark in a public lecture, Marianne’s father had gone underground to an unknown location. Then, in December 1944, Marianne’s mother got a notice to report for deportation. In desperation, Marianne went to a sympathetic neighbor for help – a Nazi party member.

Marianne knew his affiliation, but her gamble paid off. The neighbor helped get Marianne’s mother’s papers destroyed so that she no longer officially existed, and could not be deported. Marianne later learned that he had helped many Jews over the years. Marianne’s father was able to return to Munich, and the family was reunited just before the American troops arrived.

Marianne came to the US alone in 1947. She attended the University of California earning degrees in Social Welfare. She had a long career as a psychotherapist working in a private practice.

Franny Krieger

After her parents and sister were taken from their home by the Nazis, Fanny hid in a boarding school in France.

I still have our photo album which I found in the apartment on the floor after the Germans came. All those pictures are so happy.

Fanny (née Bienstock) Krieger was born in Paris in 1929. Her father, born in Poland, and her mother, born in Romania, had met in Paris. Fanny’s parents worked selling sweaters in markets in the surrounding towns. They left every morning as early as 5:00 am going to different towns each day of the week. Fanny and her younger sister Helene were sent to board with other families, and saw their parents only a few hours each week.

When the war started, Fanny’s parents cut their working hours, stopped traveling, and the family was reunited. For her mother’s health, the family moved to Aix-les-Bains town near the Swiss border which was famous for its therapeutic baths. This town, to which many Jews had fled, was occupied first by the Italians then by the Germans in 1943.

At first, the German troops maintained a very low profile, but soon a brutal reality set in. On the night of November 14, 1943, there was a roundup of Jews in the town. Nazi soldiers came to the house they had rented and took Fanny’s parents and sister. They had been betrayed by a paid collaborator.

Fanny’s mother’s cousin, visiting from Paris, was sleeping in Fanny’s bed and was arrested with the other members of the family. Thirteen-year-old Fanny was spared because she had gone to spend the night at an aunt’s.

Fanny spent the rest of the war hiding in the boarding school in Aix, waiting for the end of the war and hoping for the return of her family. But her mother and sister were killed in Auschwitz, and her father had died during a death march from Auschwitz just days before the liberation by the Americans. Cousins of Fanny’s father obtained papers for her and in 1947 she landed in New York, 17 years old and alone. Five years later, she moved to Texas, where she met her husband. They created a fly-fishing business and Fanny founded Golden West Women Fly Fishers.

Paul Schwarzbart

Paul Schwarzbart was hidden in a Catholic school.

Paul Schwarzbart was born in Vienna in 1933. He enjoyed a loving and sheltered family life with his parents, Friedrich and Sara, until the Anschluss and Kristallnacht. In the winter of 1938, 5-year-old Paul and his parents smuggled themselves into neutral Belgium, hoping to get entrance visas to the U.S. They could not. Two years later, just before the arrival of German troops, Paul’s father was arrested by the Brussels police as an undesirable Austrian.